Private lives

Laurie Smith

6 June–5 July 2025

In Private lives, Laurie Smith paints scenes that collage fantasy, history and the London painter’s own life. Queer history and contemporary nightlife blend. The show captures a moment in motion, romantically. They are scenes, unstaged, where subjects contest for focus.

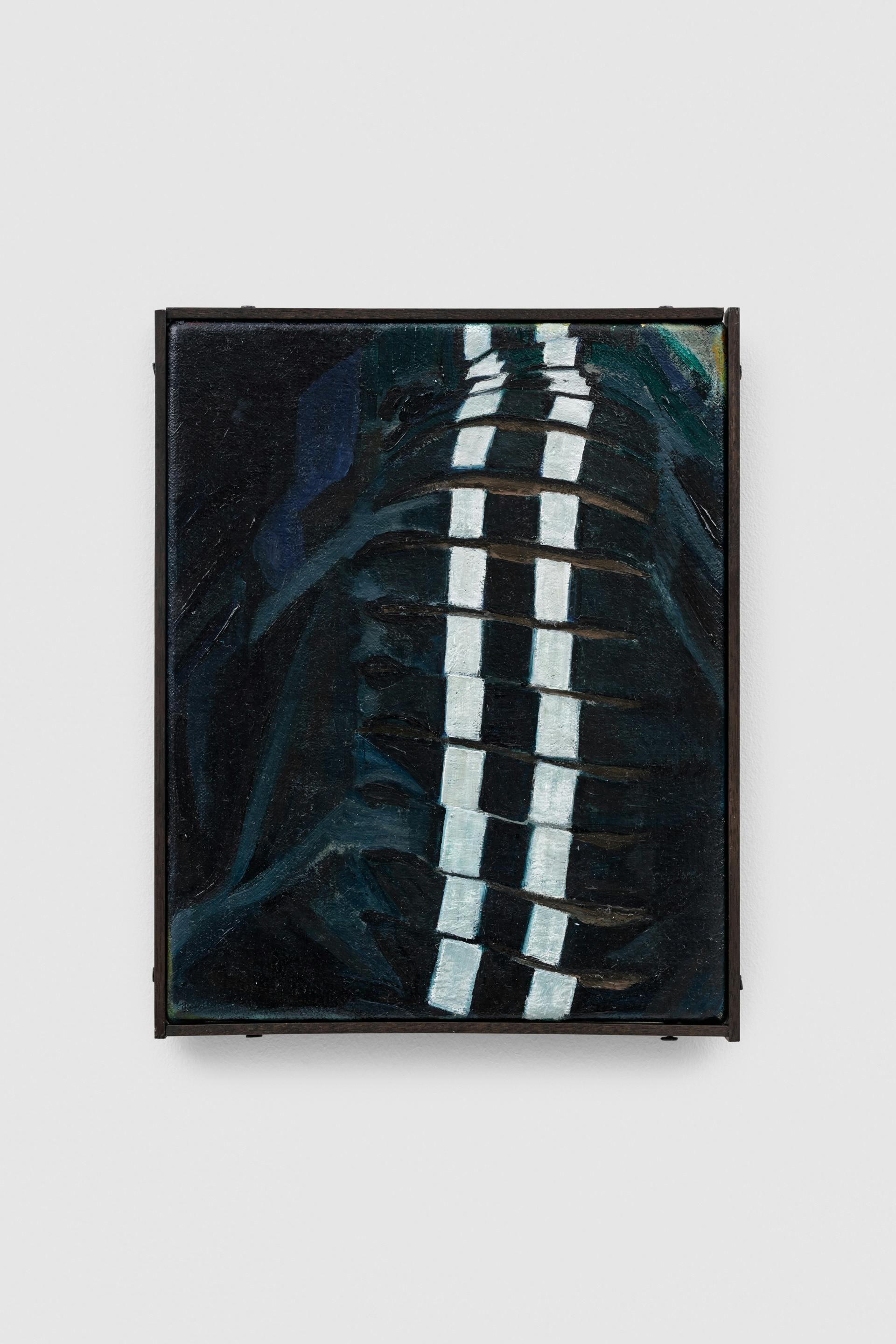

Private lives contains four works: two larger paintings (The Gemini and Boy Staring at an Apparition); one panel (Sink No Tilt); and one smaller work (Trespassers). Together, they depict, whether in the zoomed in textures of stripes in Untitled, or in the stretched movement in Boy Staring at an Apparition, different flashes of a night out.

Smith’s style draws on the moodiness and expansive vastness of the scenes rendered by Francisco de Goya. The title, in fact, of Boy Staring at an Apparition, is taken from the 1824-5 work by him. In that painting, a boy, softly rendered, gasps, open mouthed, at a figure of ghostly lightness. In Smith’s iteration, two dancers tousle on a stage. In the audience, boys stand, in denim, transfixed.

Smith builds in other references too. The bartender in The Gemini is based on a photo from the 1930s of a bartender working in Le Monocle, an iconic lesbian bar in Paris that closed in World War II. The title to the show Private lives comes from a line by Essex Hemphill in Looking for Langston, a documentary on and reimagination of the life of African American writer and poet Langston Hughes, in which Hemphill is commenting on what has been lost in the march towards sexual liberation. The pose and style of the figure in the white shirt in The Gemini is reminiscent of the 1980s ballroom scene. The stripes in the smaller untitled works are a nod to the adoption of athletics clothing in contemporary gay fashion. There is, throughout, a playful layering of fiction and the past.

The paintings in Private lives are spontaneous, urgent. The panel works are sudden, fragmentary in their composition; the framing reminiscent of pictures from a fashion runway. They hold pace. In Boy Staring at an Apparition, the two men dance on the stage. One holds the other’s crotch. The other grabs at his neck with a towel. The dancers have trousers that rush with lines of motion and light and sweat. The men dance and the space between them tips with violence and desire. Both grace and fury occupy the image.

In writing and conversation about cities and queer life, the good things are always ending. Each new party is already worse than it was. Each new gay bar is closing or losing its audience or losing its charm. Each new expression of community is more lacking or weak than the last. Every couple is breaking up. Desire starts and chokes and stops. Smith’s paintings bring together the mournfulness and movement of gay life. There is a delicateness (to romance, to community) that stems from an awareness of its future passing. Private lives contains an anxiousness and desperateness to hold on to what is leaving. In Boy Staring at an Apparition, a woman’s face breaks into two: one looks at the dancer, the other looks away, smoking. Her spectral motion flickers in the corner of the painting.

— Written by Thea McLachlan

Laurie Smith

(b.1994, Huddersfield, UK) lives and works in London. Selected exhibitions include: Parloir, Brunette Coleman, Tournai (2024), diez, Amsterdam (2024), A Flower for a Heart, Painters Painting Paintings (2024), Day by Day, Good Day, Union Pacific, London (2023), Stranger Than Paradise, VO Curations, London (2022).

Publications

Credits

Images courtesy of Brunette Coleman, London. Photography by Jack Elliot Edwards.